So are a lot of other people.

So far, all we’ve gotten is a dozen large or mid-sized lenders hiking 5-year fixed rates over the past week or so.

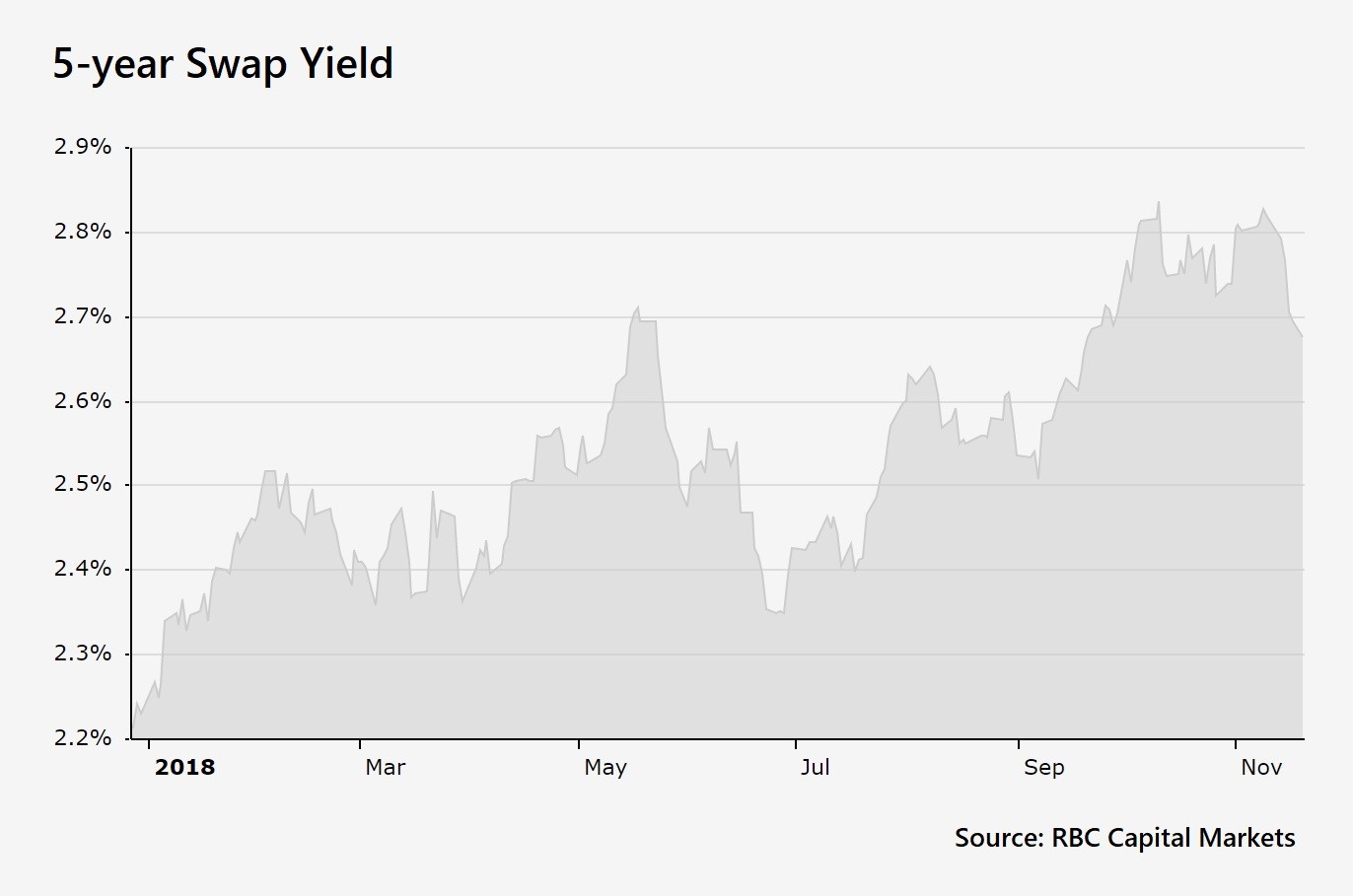

Meanwhile, the 5-year swap yield (one of the best leading indicators for fixed mortgage rates) is back down to levels it saw six months ago.

Back then (in May), the best 5-year fixed rates at big banks were roughly 3.44%-3.49%.

Today we’re at 3.69%, give or take, despite yields having dropped almost 20 basis points in the last 10 days.

No Rush to Discount

Big banks, which directly or indirectly control over $4 out of $5 mortgage dollars in this country, are in no hurry to chop rates and match falling yields. (Falling yields generally lower their funding costs.)

They’ve watched their mortgage growth get pummelled to levels we haven’t seen since last century. They’ve also witnessed a whole new level of competition this year for deposits and mortgages. That’s pressured net interest margins in the worst way.

The biggest problem is that the pool of prime borrowers has shrunk like wool socks in a clothes dryer. That’s mainly courtesy of stricter mortgage rules and higher rates.

These changes have driven competitors to cut insured/insurable mortgage margins to the bone to keep their pipelines full. Banks, which fund many of these competitors, seem to be onto them. What we’re hearing is that banks are being somewhat less generous on fixed-rate mortgage pricing for the non-bank companies they buy mortgages from.

On top of this, banks are also keeping their own discretionary bank rates elevated. Aren’t oligopolies grand?

None of this is astonishing. After all, we are in the first quarter. Q1 is a notoriously weak time for mortgage discounts as the banks keep their powder dry for the active spring mortgage market.

There’s also the never-ending headline-driven worry about the credit cycle deteriorating. If/when that happens, bank losses will tick higher. And banks being the shrewd operators they are often price for such possibilities ahead of time.

Summing it all up, mortgage rates will follow if yields drop further. But don’t expect the juicy fixed-rate discounts we saw earlier in the year—not until the banks recoup some of their spread.

log in

log in

7 Comments

I recall in late spring of 2017 some senior bank executives declared (internally) that the housing market had peaked and their subsequent decision to push borrowers down the insured channel. Of course borrowers had other ideas as there was a big incentive to go uninsured to bypass the (then new) stress tests for high ratio mortgages. I’m sure Rob can bring up the stats on how much the insured market dropped last year vs how much the uninsured side increased. That’s part of the reason why the Banks later welcomed the stress testing on uninsured loans. They were concerned that people were using unconventional methods to come up with funds just so they didn’t have to be stress tested. They clearly saw that as a risk. Today they continue to push borrowers through the insured channel by offering preferential pricing on high ratio loans and, as stated in the article, it doesn’t look like that’s changing anytime soon.

It reminds me of prices at the pump whenever crude oil prices plummet. The price hikes are always lightning-fast but they fall back down like a feather in a windstorm.

Hi Yolo,

Without commenting on the rest, out of the 2017 borrowers who originally planned to go insured, what’s your guess on the percentage of those who decided to go uninsured to avoid the insured stress test?

And what do you define as “unconventional” methods of funds?

Just curious. Thanks….

Hey Brett, Yep, sometimes its like a windstorm with a thermal updraft and four 747 jet engines pointed straight up.

I can’t recall the exact numbers but I found the article below saying that as of Aug’17 the insured market dropped 4.5% and the uninsured grew 17.3%. I know there was a better article that showed the numbers for the entire year but I wasn’t able to find it on a quick search. As for what percentage of that 17.3% growth was comprised of people who were originally intending to go insured, I’m not sure that specific figure was published. It was more a commentary on the trend.

“Unconventional” in this case means borrowing from parents, relatives or private lenders that don’t show the loans on a credit report.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/osfi-mortgage-rules-1.4358048

Specific quote from that article:

“Uninsured mortgages, meanwhile, grew 17.3 per cent — which suggests homeowners were doing anything they could to get their down payments above the 20 per cent threshold, and away from being locked out of an insured mortgage from failing a stress test.”

Hey Yolo,

In 2017 the insured market dropped (relative to uninsured lending) mainly because the DoF banned insurance on refinances, extended amortizations, $1 million+ properties and rentals. And also because of OSFI’s draconian capital requirements making LTVs over 70% far less economical to insure.

As for parental gifts/loans being unconventional, they’ve been convention for years (albeit more popular in the 2000s), so I have to differ with you there. As for private mortgages behind uninsured firsts, lenders have always included the payment of a private mortgage in debt ratio calculations. So again, I’m not sure how getting a private loan would help federally-regulated borrowers in any material way.