In 18 days the Fed is expected to do what it’s virtually never done: inflate the U.S. economy with a rate cut — despite 50-year lows in unemployment and record highs in stocks.

In 18 days the Fed is expected to do what it’s virtually never done: inflate the U.S. economy with a rate cut — despite 50-year lows in unemployment and record highs in stocks.

Some argue the Fed is dangerously veering off its normal course, that Trump’s browbeating of Powell is working.

The risk is clear: more inflation. And inflation is the assassin of low rates. (Rising U.S. inflation is ultimately bullish for Canadian mortgage rates given we’re in bed with each other economically.)

That risk is heightened if a U.S./China trade deal is announced, wage growth breaks long-term highs or other inflationary triggers materialize.

The threat can’t be dismissed, despite worrying recession signals. Core inflation is already rising above the mid-point target, both in Canada and below the 49th.

Mind you, inflation expectations would have to close in on 3%+ for borrowers to feel significant rate pain. And the yanks haven’t averaged 3%+ core inflation in any year since 1995. That’s why the bond market is completely unprepared for such a possibility. Rates would climb a wall at the mere hint of core CPI with a 3-handle. “We should not underestimate the speed with which the market can reprice,” warns Franklin Templeton’s CIO, Sonal Desai.

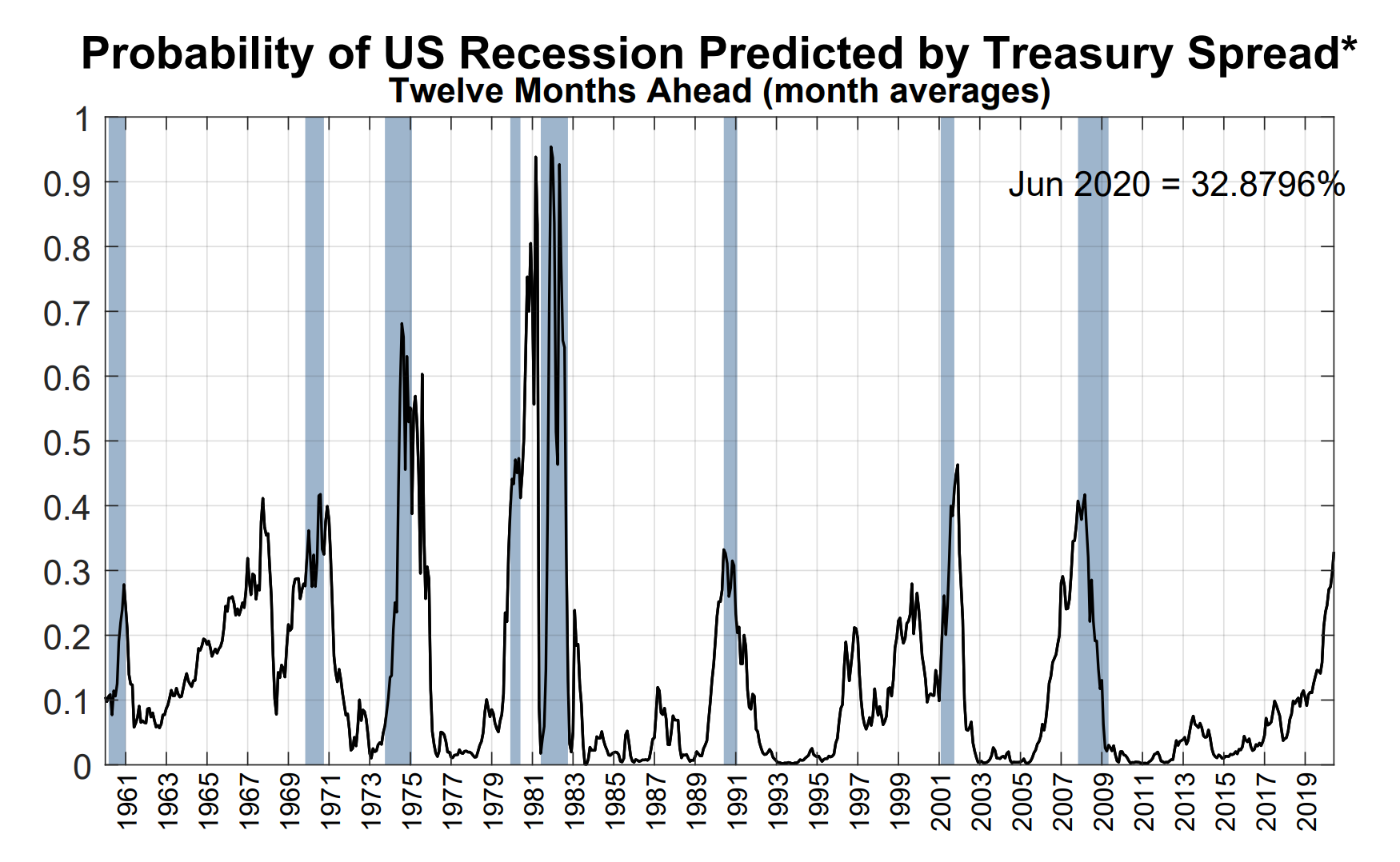

Note that the chances of a recession next year are one in three, estimates the New York Fed. But that’s still a two in three chance of no recession.

Source: New York Federal Reserve

Meanwhile, the Fed chair assures us, the economy is “in a very good place.”

We’re Not at DEFCON 1 Yet

Lord no, inflation’s not even at DEFCON 3 — i.e., it’s not time to panic about surging rates. North America’s economy has lost steam overall, it’s caught in a long-term disinflationary cycle and there are downside risks O’plenty. There’s a reason traders say, “don’t fight the Fed.” Next year rates could be at new lows for all we know.

The message above is merely a reminder that virtually any rate scenario is possible over a five-year span in a random walk economy. It was just seven months ago the Fed was talking about multiple rate hikes this year. And rate cuts are inflationary, despite core CPI’s long-term downtrend.

The answer to uncertainty is always the same: risk management. Today you’ve got fixed rates ~20 bps below variable rates. Which would you pick if the risk of much higher and much lower rates were theoretically equal?

Risk mitigation (locking in) is most appropriate to those mortgagors with low savings rates and minimal liquid assets to fall back on.

More Rate & Housing Reads

- Fed’s Evans: Expect at least “a couple” U.S. rate cuts

- Goldman: “…Delivering rate cuts, even when priced [in], tends to raise expectations of subsequent cuts” (sub.)

- Scotia: “We believe the Bank of Canada is unlikely to follow the Fed as it cuts rates.”

- Imagine inflation’s effect on a junk-bond bubble: “In a negative-yield environment, you can no longer buy bonds to hold them to maturity because you’d be guaranteed a loss. You’d have to buy them solely on the hopes of even more deeply negative yields…”—@wolfofwolfst

- Joe Public often outguesses the experts on rates

- That formerly inverted yield curve just steepened the most in three years

- “The stronger Canadian dollar is great for cross-border shoppers but eventually it becomes hazardous for the domestic economy.”—Scott Barlow

log in

log in

Lord no, inflation’s not even at

Lord no, inflation’s not even at

7 Comments

Is it possible for the Bank of Canada to be raising rates while the Fed is cutting rates?

I have to wonder how much of that higher inflation is due to tariffs?

While inflation does influence interest rates, interest rates also influence the currency, which partially counters the original increase in inflation.

Hi Ken-y,

Yes indeed. The last time it happened was 2002. By 2003 the BoC was cutting again.

Hi Matt,

Higher tariffs are already inflating prices somewhat, but eventually they become a drag on growth—which is disinflationary.

In May BMO Economics wrote: “The estimated 1-per-cent slowing in U.S. GDP due to current duties and possible further protectionist moves could translate into 0.5-per-cent-less Canadian output, based on the estimated impact of a change in U.S. growth on Canada.”

There are all kinds of feedback loops that trade wars create (including exchange rate impacts) but in general, tariffs create somewhat offsetting inflation effects over time. Their biggest potential for swaying rates near-term is if tariffs drive up inflation expectations, which would add more reason for a BoC hike.

That’s true Ralph, albeit it’s the inflation triggers that drive U.S.-Canada interest rate differentials (and hence, currency fluctuations) which usually have the biggest impact on mortgage rates.

My favourite response to the threat of loonie appreciation was from BMO’s Doug Porter: “The loonie is starting from a soft level. The market is already assuming the Fed will do more than the Bank of Canada in the way of cuts. And is anyone seriously concerned about the Canadian dollar getting too strong?”

Poloz now seems to be underestimating growth at 1.5% in Q3. My guess is he’s doing that so he can say growth exceeded forecasts and thus have more justification for a rate increase. It’s pretty sad that we’re even talking about the possibility of higher rates with GDP so dismal.