The wait for good news on trade is over. The U.S. and Canada reached a last-minute deal on Sunday to replace the current North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). And we’re seeing the rate effects already.

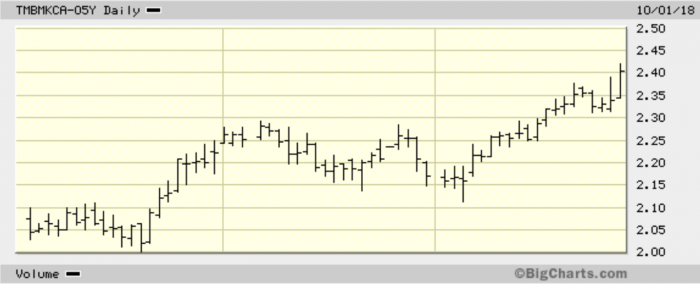

Canada’s 5-year bond yield, which steers fixed mortgage rates, has rallied to a fresh seven-and-a-half-year high.

The new deal, called the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), is expected to be signed as soon as November 30, after which each country’s legislature must approve it. The pact is far from perfect but it’s way better than no deal at all, given we rely on Americans to buy 75% of our exports, says National Bank Economics. The prospect of more tariffs (especially auto tariffs) have been a dark cloud on Canada’s economy for months.

Borrowers Beware

The market will view this deal as more inflationary than not, so other things equal, yields could remain supported near-term. That means you’ll want to lock in a rate pronto if you need a rate guarantee and haven’t got one already.

Our intel from lenders and brokers suggests over three-quarters of borrowers are taking 5-year fixed rates at the moment. That’s notable as more lenders announce fixed-rate hikes this week.

The best 5-year fixed rates are still in the low 3% range if you need an insured mortgage or have 35% down. Uninsured mortgages, which are required for refinances, investment property financing, million-dollar home purchases or 30-year amortizations, are in the mid-3% range….for now.

There’s a good chance the 5-year yield could approach 2.50% before too long. That would take 5-year fixed rates up another 15+ basis points, which would cost 5-fixed borrowers $1,780 more interest over their term on an average $250,000 mortgage.

The biggest impact could come if/when banks up their posted 5-year fixed rates. That’s now a more distinct possibility in the next few weeks. This would make it even harder to pass the government’s mortgage stress test, and shut out incrementally more homebuyers and prospective refinancers.

log in

log in

6 Comments

Hmmm… this is the second time it has been mentioned that prospective homebuyers will be “shut out” because of the stress test. But people don’t stop buying just because they qualify for a lower amount – they just buy a cheaper product. In fact, when enough people buying at the margin (of their affordability) are reduced, this will eventually serve to reduce prices until they match the supply of buyers (or more specifically: available credit). Therefore gradually rising rates would have a net neutral impact to the majority of buyers who are not borrowing at the limit. They will now be able to purchase the same product at a lower price to offset the higher financing cost. In fact, the stress test goes one further by restricting credit by assuming a higher interest rate and therefore restricting credit (and hence prices) and implicitly improving affordability.

Understandably, a small number of refinancers will be negatively impacted, but this is much more a consequence of tighter lending standards which the banks are intentionally implementing as a result of the contracting credit cycle. This may be a good thing for those who are at the very edge of affordability and perhaps should not be granted further credit anyways. Higher rates, the stress test and tighter lending standards serve to increase the quality of credit in the financial system, which is no bad thing.

Hi Yolo,

Thanks for the comment. Intelligent counterpoints like yours are always welcome and appreciated.

In the passage you quote, focus on the word “incrementally.” You’re totally right that many will buy cheaper properties. But many won’t. Many Canadians simply won’t be able to afford a suitable property where they want (or need) to live. And for some, long-distance commuting isn’t optimal. Hence, many would-be buyers will be forced to stay renters or parental spongers–potentially while home values rise all around them.

And we can’t forget, all that extra demand for “cheaper” properties, in time, makes those properties not-so-cheap. That’s exactly what’s been happening as a result of recent regulations.

As for the supply of buyers dwindling and bringing down prices, one has to remember two things. One, people keep flowing into our biggest cities each and every day (think immigration and intraprovincial migration/urbanization). That reinforces the buyer ranks. Second, people eventually adapt. In 1-5 years, many of today’s stymied buyers will come back into the market, having saved up more income, secured a co-borrower or raised bigger down payments. Prices will then bounce back, eliminating any short-term “neutral” impact (if such a thing actually exists).

Regarding the effect of rates on the majority, again I agree. But that is not related to the story’s point about the minority (again, focus on the word “incremental”).

Last but not least, you’re 100% right that stricter lending improves the quality of borrowers…..at banks. But not all borrowers use mainstream lenders. To think that people will stop over-borrowing because of B-20 or insurance restrictions is like saying smokers will stop smoking because the government puts black lung pictures on cigarette packs. People overborrow because they’re debt-addicted or because they have unavoidable life events. Mortgage regulation solves neither problem. It only defers it and/or pushes such borrowers into the arms riskier, higher-cost lenders.

The DoF and OSFI may be well intentioned, but many would argue the side effects, and ultimate outcomes, are worse than the disease. And we haven’t even got into a discussion of the damage to liquidity and competition.

Yes, you’re right – people will eventually adapt, both buyers and sellers. It can take 6-12 months (or maybe even longer) before the market reaches equilibrium from impacts such as short term interest rate rises. That’s why you’re seeing excessive demand for “cheaper” properties (i.e. condos). Rising rates have had an immediate impact on buyer affordability but they haven’t yet been factored into prices across the entire spectrum of the market. However, this is a transitory trend being fuelled by people either unable or unwilling to wait to buy. Eventually, as the prices of more expensive properties adjust to meet the supply of buyer affordability (credit availability), you will see both the demand and price pressures on the lower end start to subside. This isn’t something unique to Canadian cities.

The well intentions of OFSI and DoF that you refer to are to protect the loan books of the systemically important financial institutions (the “banks”) in the event of a liquidity crisis. This is why many non-banks including credit unions are taking the same measures even though they’re not required to. The impact to borrowers who choose to over extend themselves on credit using alternative options (private lending, mortgage investment companies, etc.) are not considered material to the financial system due to the relative market size. The regulations haven’t shut out market participants so much as they have forced lenders to revisit their underwriting practices. Consumers should take note and reconsider their current and future borrowing position. Many won’t though and the impact to some of those borrowers will be very real and unfortunate – “give them enough rope” and all that. But hopefully that will only be the case for a very small number of people. For everyone else it will be a case of small gradual adjustments.

Hey Yolo, how on earth do you know demand and price pressures on the lower end will start to subside? That is pure speculation. First time buyers, investors and people on the wrong end of B-20 will keep snapping up everything under $800-900,000 in Toronto and Vancouver. There is nothing to suggest otherwise. The more rates go up, the more demand flows to condos and townhomes in this price range because that is all the middle-upper class can afford.

Those “well intentions of OFSI and DoF” have warped the market by shifting demand to lower end homes and artificially raising their prices. You think that is good for banks? Think again. It’s called collateral risk.

How does imposing a stress test on straight switches “protect the loan books of the systemically important financial institutions in the event of a liquidity crisis?” That is just bad short-sighted policy and one more example of regulator overkill.