Never before has Canada’s banking regulator received so much pushback on a mortgage rule. OSFI has felt such heat from its controversial “B-20” stress test, that it’s started a campaign to defend its position—e.g., this speech last Tuesday (video) and this one last Thursday.

From that and from what we know of regulators’ non-public comments, one thing appears clear. The government has no desire to relax B-20 if it means homeowners taking on more debt.

That said, there are important B-20 revisions that would materially improve borrowers’ finances without Canadians becoming more leveraged. Policymakers would do well to listen to that feedback because—as history has shown—officials don’t always have a monopoly on foresight.

But first, let’s look at what led up to Ottawa adopting this game-changing new mortgage rule.

The “Safety Buffer”

“The stress test requires a borrower be qualified for their mortgage with a [safety] buffer of affordability built in — to ensure they can continue to pay their mortgage if conditions change,” explained Assistant Superintendent Carolyn Rogers last week.

She listed three things that could keep people from making their mortgage payments in the future:

She listed three things that could keep people from making their mortgage payments in the future:

- “a rise in interest rates that increases their payment obligation”

- “loss or reduction of income”

- “an increase in other, non-mortgage expenses.”

But what casual onlookers don’t know is that Canada has always had a stress test. Lenders have always had a debt-ratio test that, if exceeded, resulted in the borrower being declined for a mortgage.

In its various incarnations, that debt-ratio test (for simplicity, let’s call it the “old stress test”) served Canada well for decades.

But then something changed at the turn of the millennium.

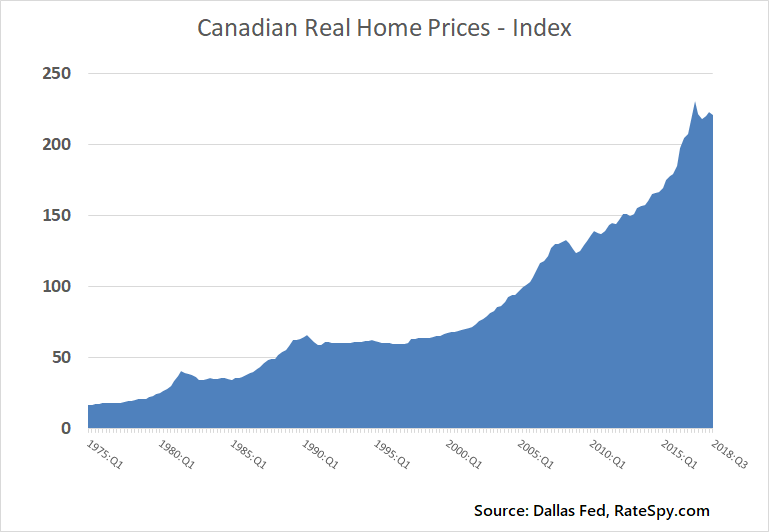

Real (inflation adjusted) home prices started ramping.

The percentage of people getting hefty mortgages relative to their income—which the Bank of Canada calls “highly indebted borrowers”—surged. The ratio of new mortgages with a loan-to-income ratio over 450% (the BoC’s threshold for highly indebted) peaked at 19.4% in 2016, right before stricter stress testing began on insured mortgages.

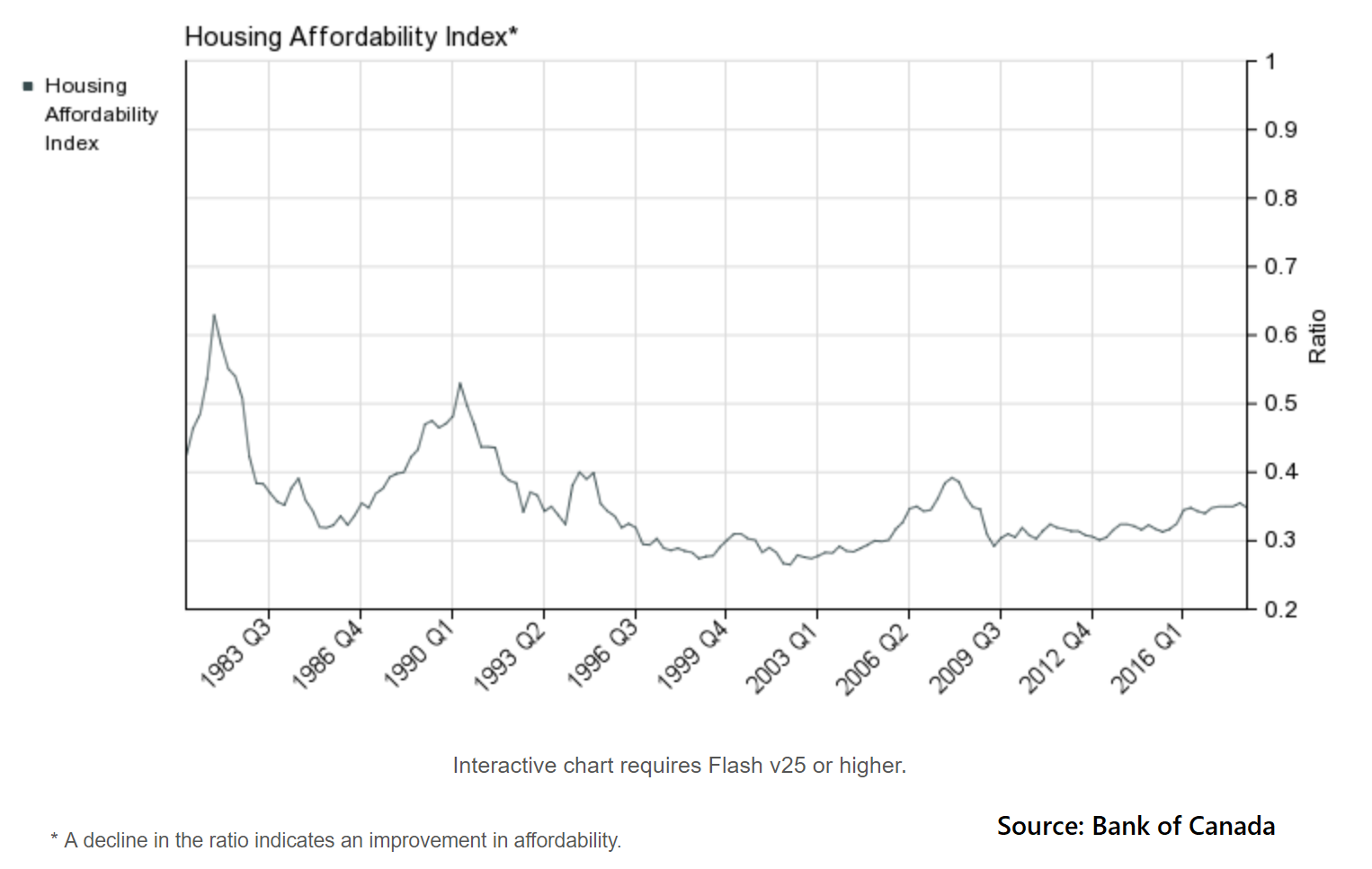

There lies an important distinction, however, between the amount of debt someone carries and their ability to service that debt. For that reason, the jump in highly indebted borrowers did not mean that people couldn’t make their payments. Falling interest rates and rising incomes kept payments reasonably within historical tolerances. These offsetting factors ensured that the actual share of disposable income put towards housing costs did not climb like home prices did.

(Note: Housing costs versus income were unquestionably higher in places like Greater Toronto and Vancouver. But prices in those regions were more fuelled by higher incomes, under-supply, net migration, equity-rich repeat buyers, foreign investment, etc.)

It’s important to note that all “highly indebted” prime borrowers were approved for mortgages pursuant to the government’s previously established and long-standing debt-ratio guidelines.

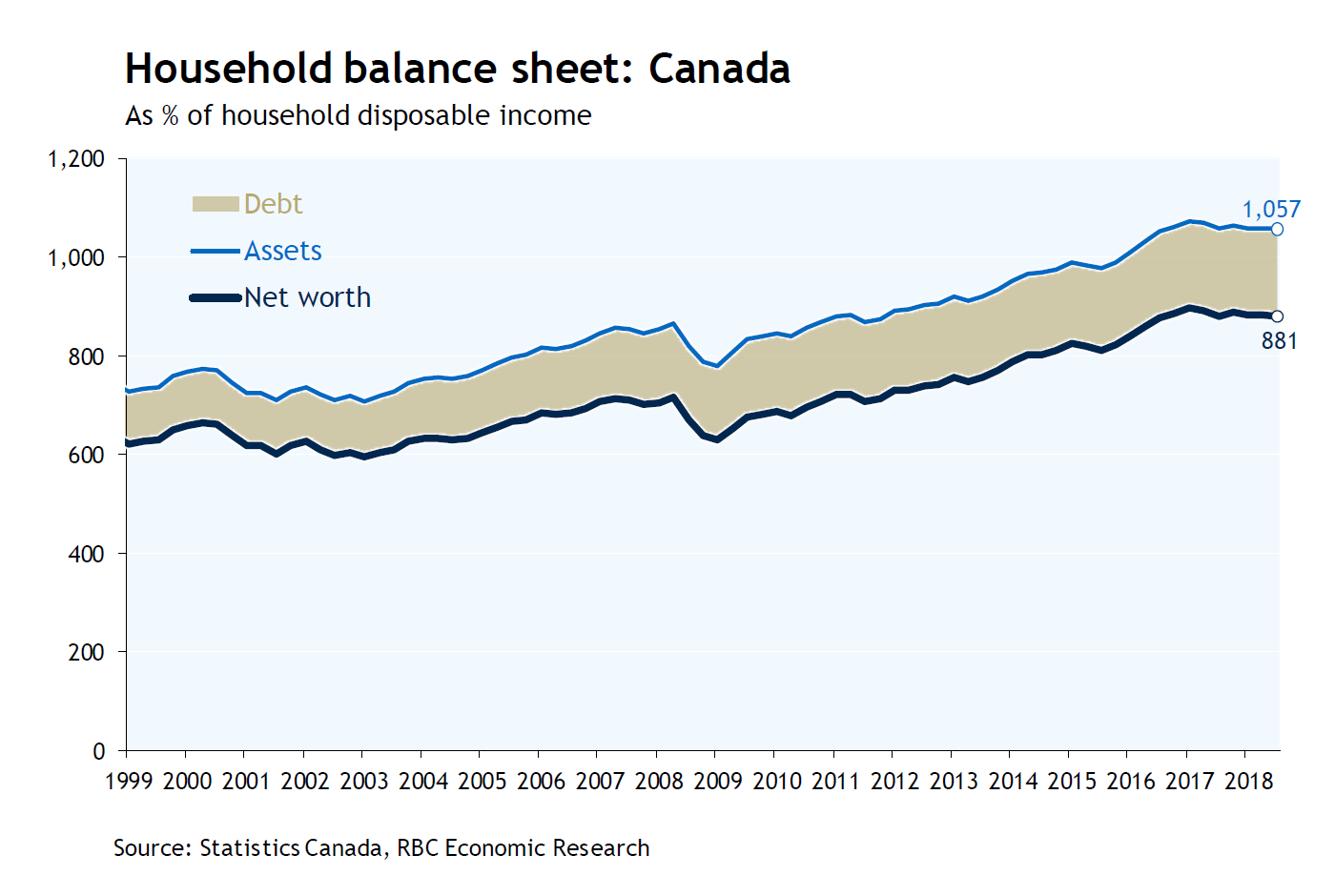

But homebuyers’ total debt was growing too fast for policy-makers’ comfort. They pointed to research suggesting that elevated debt-to-income ratios degrade macroeconomic performance and stability.

Officials took little solace in the fact that net worth also kept climbing. OSFI viewed surging home equity as potentially fleeting in the event home prices dropped considerably.

This brings us back to the old versus the new stress test.

A 200 bps Buffer for Future Interest Rates

The new mortgage stress test was largely designed to protect borrowers against “a rise in interest rates that increases their payment obligation,” Rogers said.

That was the case with the old stress test too. Officials and lenders set guidelines on the total debt service (TDS) limit decades ago to account for higher rates, unforeseen borrower expenses and income interruption.

In years gone by, regulators could have set prime mortgage TDS limits at 50% (today’s limit for most institutional non-prime lending), but instead they settled on a more conservative 40-44%, and it’s been that way for years.

Nonetheless, regulators didn’t feel that their old stress test was conservative enough. OSFI wanted borrowers to prove they could afford rates that were 200+ basis points above their actual rate. Why? Because “interest rates…remain at historically low levels,” Rogers said. The implication, of course, is that rates could rise back to their historical long-term average.

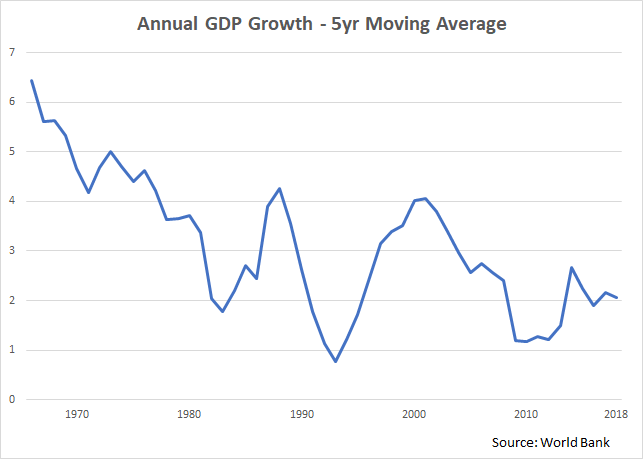

What policy-makers never acknowledged, however, is the fact that low rates could well be the new norm.

“…We have to have an honest discussion on whether or not today’s homebuyers are being stress tested against rates that are realistic,” said John DiMichele, chief executive of the Toronto Real Estate Board (TREB) in a statement last Wednesday.

But Rogers made OSFI’s position clear. “We’re not really in the business of forecasting at OSFI,” she said.

On the other hand, she did allow for future revisions to the stress test. “Should that ‘margin of safety’ be monitored, and should changes be considered if conditions in the environment change?,” she asked? “Of course they should.”

And that’s interesting because setting policy to guard against an extraordinary jump in future rates is, by definition, forecasting the probability of an extraordinary jump in future rates. And if you’re going to assume such an event and use that to create far-reaching policy, you better account for modern-day rate catalysts.

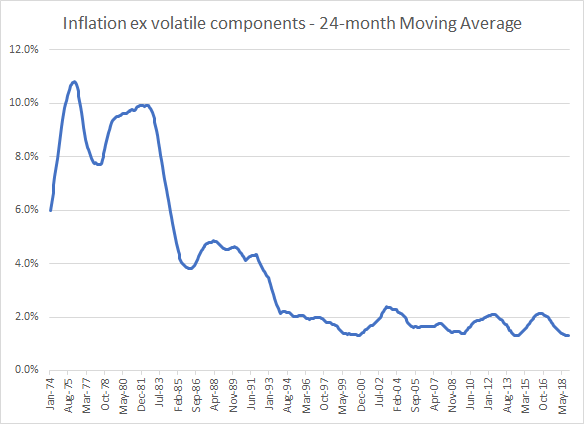

Like past arrears rates, historical interest rates arguably have less predictive power than they used to. Times have changed—drastically—both with economic growth…

…and inflation.

With modern monetary policy (the BoC’s 2% inflation target) and structural impediments (the ‘Amazon effect,’ demographics, offshoring, etc.) suppressing runaway price growth, some believe Canada will never see prime 5-year fixed rates hit 7%+ again for decades.

To breach that level, core inflation would have to surge above the BoC’s 3% limit and hold there, something it hasn’t done for almost three decades. Alternatively, the market would have to believe the Canadian government was in danger of defaulting on its debt, an implausible scenario in the next decade-plus given the country’s taxing authority.

By definition, historical rates reflect past economic trends. It’s notable, then, that OSFI relied on historical rates to make policy decisions, but when it came to relying on other telling historical metrics (e.g., arrears), Ms. Rogers discounted that as a “rear-view mirror” indicator. That’s led many in the industry to ask, does the regulator have a bias towards data that makes its case?

Justifying 200 Basis Points

For the reasons above, historically low levels of interest rates are a questionable reason to throw out the old stress test and replace it with a version that’s 75% stricter. The old stress test survived 20% interest rates of the 80s (a time of less consumer debt but not a time of drastically lower debt ratios).

Failing to acknowledge new rate realities could ultimately prove detrimental to economic performance. If rule over-tightening reinforced a recession, that would make it even harder for people to pay their mortgages. That, in turn, would heighten risk for banks, the exact opposite of OSFI’s intention.

In many people’s minds, putting the brakes on home price growth might be a more logical reason for a new stress test. But to this end, Rogers said “we don’t take a particular view on house prices” and “B-20 was [not] designed to target escalating home prices.”

All this said, disbanding the stress test altogether would be foolish given Canada’s growing debt risks. OSFI was right to trade the old stress test for a new more conservative version, at least on homebuyers and refinancers increasing their debt loads. Albeit, the qualifying interest rate used for the stress test is debatable given the above.

OSFI also cited income loss and unexpected expenses as justification for its hefty 200-bps stress test. Those too are valid concerns. We’ll dig into these risks in Part II.

log in

log in

Never before has Canada’s banking regulator received so much pushback on a mortgage rule.

Never before has Canada’s banking regulator received so much pushback on a mortgage rule.  A 200 bps Buffer for Future Interest Rates

A 200 bps Buffer for Future Interest Rates

7 Comments

Thank you for this insightful overview of the stress test and what got us to this point. It’s clear OSFI is displaying a bias towards introducing new policy without having fully proven its need nor effectiveness.

Hope you guys continue to hold their feet to the fire on this, and hopefully they’ll see the error in their ways and make the needed tweaks to what is otherwise flawed policy.

Looking forward to part 2.

It’s notable that the osfi response to criticism has covered only some of the arguments, and is ignoring others, such as.

– if rates do rise by 2 points then it should also be expected that incomes will have grown.

– a smaller issue: the stress test over-estimates how much the future payment would increase. Eg. if the rate is 3.34% for the 1st 5 years then rises to 5.34%, the stress test over estimates the future payment by 3.4%

– an argument i have never considered but is implicit in your comments: why does the test have to be done at 32% gds and 44% tds.

– in the event of that 2 point rise, in most cases payment stresses could be alleviated by extending amortization by 5 years or so.

– should osfi be concerned about the negative economic effects of the stress test. Is osfi correctly trading off the relatively high probability of economic harm (which is a risk factor for the entities it regulates) versus the low probability of a 2 point rise in rates.

Calls to eliminate the stress test are mainly from self-interested parties so I don’t give them much weight. Though I agree there may be a case for changing the qualifying rate since 1/5th of Canada’s economy is tied to real estate and you don’t want to make a mistake on this kind of rule. It would be easier if someone could accurately model the long term effect of the stress test on employment. If OSFI wants to be more transparent as it says, it should share its data on this.

Mark – in response. I have modeled that as a result of the stress tests, by mid 2021 employment in Canada will be 200,000 lower than it would otherwise be. If you’re aware of alternative models I’d love to see them.

Thank you Will. Is -200,000 enough to cause more risk to banks than they would have faced if the stress test hadn’t happened? I don’t have any data on it but my sense is probably not.

What about the national housing act affordable housing for all. This stress test puts that put of reach for most Canadians. Only short term variable rates which can still be locked in before rates go up would really be a cause of impact. 5year or 10 year mortgage would not be especially on fixed rates until time of renewal. 200 basis poi t marker then becomes negligible unless they haven’t paid down their mortgage and hefted up all other debts. I feel needs to be looked into, this unfairly affects all Canadians access to affordable housing and is a breach of the act.

If you want affordable housing go on government assistance. Those are the only Canadians CMHC seems to care about when it comes to housing accessibility. Damn the working class.