Big bank posted mortgage rates are like sticker prices on new boats. Almost nobody pays them.

Today’s typical 5-year posted rate is 4.64%. Were you to get stuck paying this joke of a mortgage rate, it would cost you $10,394 more interest every five years, for every $100,000 of mortgage. That’s compared to the average street rate, which is almost 220 basis points lower at 2.45%.

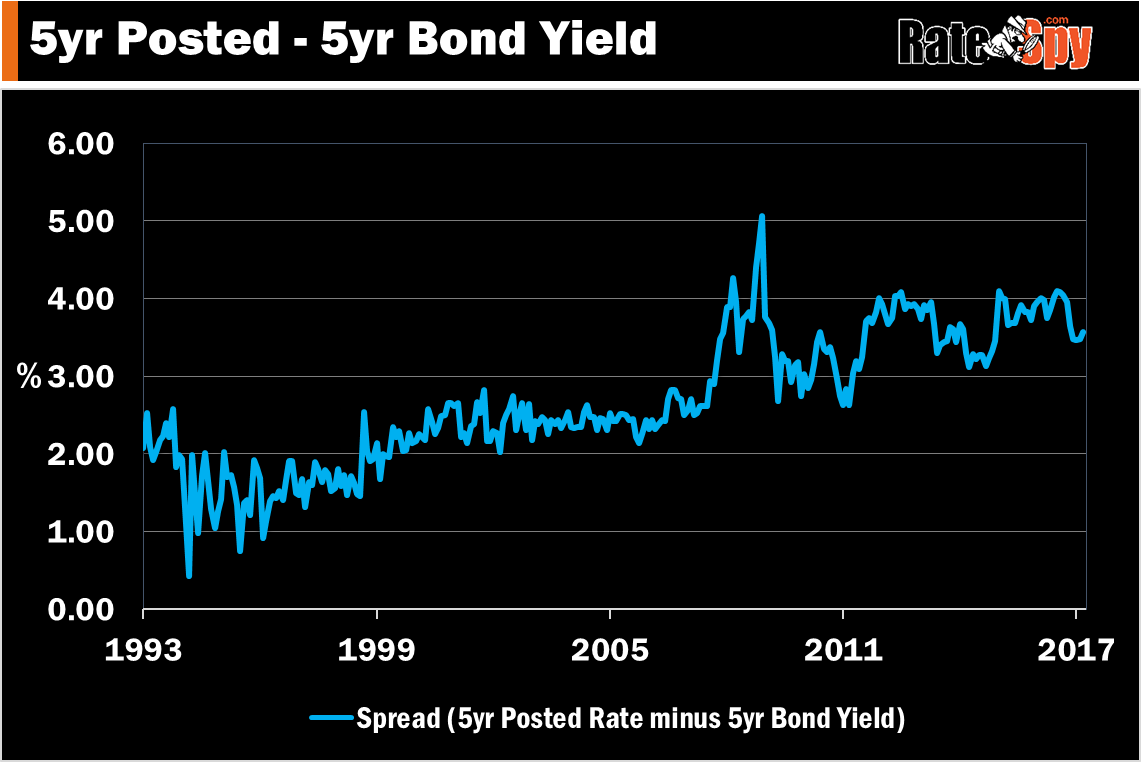

Posted rates have become so far detached from reality that they’re almost irrelevant. Have a look at this chart below.

Back when paying the posted rate was more commonplace, the spread between posted rates and 5-year bond yields was tight. But then in the late 90s it started to widen, and it widened further in the mid 2000s.

Nowadays, the spread is so wide that posted rates have little usefulness as an indicator of mortgage pricing.

So what are posted rates good for?

To the uninitiated, posted rates make a bank’s discounted rates seem like a steal.

But aside from being an inflated starting point for rate negotiations, posted rates do have more meaningful functions.

For one thing, the Big 6 banks’ posted rates are used to calculate the benchmark qualifying rate. That’s the rate lenders use when checking if you can afford higher payments (in the event that rates rise). This “stress test,” as they call it, applies to all default insured mortgages and (as of January 1, 2018) all uninsured mortgages at federally regulated lenders, like banks.

How the “benchmark qualifying rate” is calculated: Every week the Bank of Canada takes a mode average of the posted 5-year fixed rates at the Big 6 banks. That becomes the qualifying rate, which has been stuck at 4.64% since September 2016 (as of the time this was published).

Mortgage penalty calculations

If you’ve ever broken a fixed rate early, you may be painfully aware of another use for posted rates.

Lenders use their posted rates to calculate mortgage penalties. If you terminate a fixed mortgage before maturity, lenders make you pay the higher of either three-months’ interest or the Interest Rate Differential (IRD).

TD explains the IRD calculation as being:

The difference between your annual interest rate and the posted interest rate on a mortgage that is closest to the remainder of your term, less any rate discount you received (at origination), multiplied by the amount being prepaid, and multiplied by the time that is remaining on the term.

Big banks’ IRD penalties are punitive with a capital “P.” Essentially the text in red above means that the bank is comparing the rate you’re paying to a much lower rate that doesn’t actually exist. That artificially widens the spread (rate differential) and inflates your penalty. Banks don’t make $10 billion per quarter by accident.

Other Uses

Posted rates are also used for:

- Cashback mortgages — A small percentage of borrowers pay high posted rates in exchange for a cash rebate on closing (these are generally a bad deal)

- Rate Drops — Some banks guarantee you the lower of the rate available at the time you apply or at the time of closing. Rate drops are often based on the posted rate. Of course, this only matters when rates are falling (since lenders otherwise guarantee your rate at the time you apply).

- Capped variable rates — Some variable mortgages have an upper limit that’s based on the posted rate. It’s called the interest rate “cap” and your rate can never go above this number.

- Non-conforming loans — Higher-risk borrowers who can’t qualify for prime bank rates are sometimes offered the posted rate.

- Auto-renewals — There are still lenders who like to fish for suckers by putting posted rates on their renewal letters. Banks know that 39% of renewers simply take their bank’s first quote without negotiating (Source: Mortgage Professionals Canada).

The Thing to Remember

Unlike market rates, 5-year posted rates haven’t fallen much since 2014. Among other things, that’s partly because:

a) Banks make more on penalties when posted rates remain elevated

b) The Department of Finance wants posted rates to remain higher. This cools the real estate market and makes it tougher for over-indebted borrowers to qualify for mortgages (regulators’ mission these days).

Today’s high posted rates generally mean little when you’re mortgage shopping, with one exception. If you choose a lender that uses your “discount from posted rate” to calculate its penalty (like all the major banks do), and it’s a fixed mortgage, you’re potentially facing a nasty prepayment charge if you break that mortgage.

Remember this when comparing a major bank rate to the rate of “fair penalty” lender because harsh IRD penalties can easily negate a 1/4%, or sometimes even a 1/2%, rate savings.

log in

log in

If you’ve ever broken a fixed rate early, you may be painfully aware of another use for posted rates.

If you’ve ever broken a fixed rate early, you may be painfully aware of another use for posted rates.

6 Comments

I plan on putting down more than 20% as a down payment will I have to go through the stress test or is that just for mortgages with less than 20%?

Hey Jeremy,

Generally speaking, if your down payment is at least 20%, the only lenders stress testing borrowers are lenders that have to insure all their mortgages in order to securitize them (i.e., resell them to investors). Such lenders must confirm you can afford a payment at the Bank of Canada’s 5-year posted rate because that is now a federal rule for insured mortgages.

The major banks don’t have to sell all their mortgages. So they don’t impose the stress test if the loan-to-value is 80% or less.

I get that risky borrowers would have limited borrowing options and be required to borrow at rates higher than the going market rates to account for that extra risk. But do banks actually try to stick well-qualified (but uninformed) borrowers with posted rates (or rates that aren’t far off)?

It seems really wrong that two borrowers who are equally qualified could be paying two very different rates based only on the fact that one has done his homework and fought for a lower rate while the other is paying 4.-something percent because he doesn’t know any better.

Hi Shaun,

It happens far less frequently today than it once did, but some banks still offer posted rates to certain customers on certain terms. Generally, however, the banks are more competitive than that.

Keep in mind, there are banks using sophisticated technology to identify which renewing customers are rate sensitive and which are not. The folks who aren’t generally get worse initial offers. That’s just the reality of the mortgage market today. As time goes on, renewal offers will get slightly more aggressive because the internet has decreased search costs for consumers, and banks don’t want to lose credibility by overquoting.

I’ve checked out some of the rates on your site and I’m surprised by some of the great offers for 5-year fixed rates. It’s kind of making me wish I had spent more time doing some research before buying a house three years. I went with RBC’s offer of 3.14% for a $330k 5-year fixed rate mortgage. I know you don’t have a crystal ball, but is it likely that in a little less than two years from now when I renew I’ll be able to find rates at around what we’re seeing today..maybe 2.14%?? I feel like I’m really overpaying.

Hey CJ, The chances of rates staying this low (or dropping) are probably at least as good as the chances of rates increasing. Even if rates do head up in 24 months, the increase won’t be extreme. I have no reliable sense for what the future holds but if I were a betting man, I’d wager you’ll be able to renew into a lower rate than 3.14% (albeit perhaps not a 5-year fixed). This assumes you’re well qualified of course.