Do you care if some investor in China or France dumps Canadian bonds?

Do you care if some investor in China or France dumps Canadian bonds?

Many would answer, no.

But when foreign demand for Canadian bonds drops, other things equal, bond prices drop.

And given bonds and yields (interest rates) move inversely, and given fixed mortgages are partially funded in the bond market, when overseas demand for Canadian bonds falls, it usually pushes up Canadian mortgage rates.

After this recent Globe and Mail story on the Japanese purportedly buying Canadian bonds and driving down our mortgage rates, we had a look-see into what other foreign investors were up to.

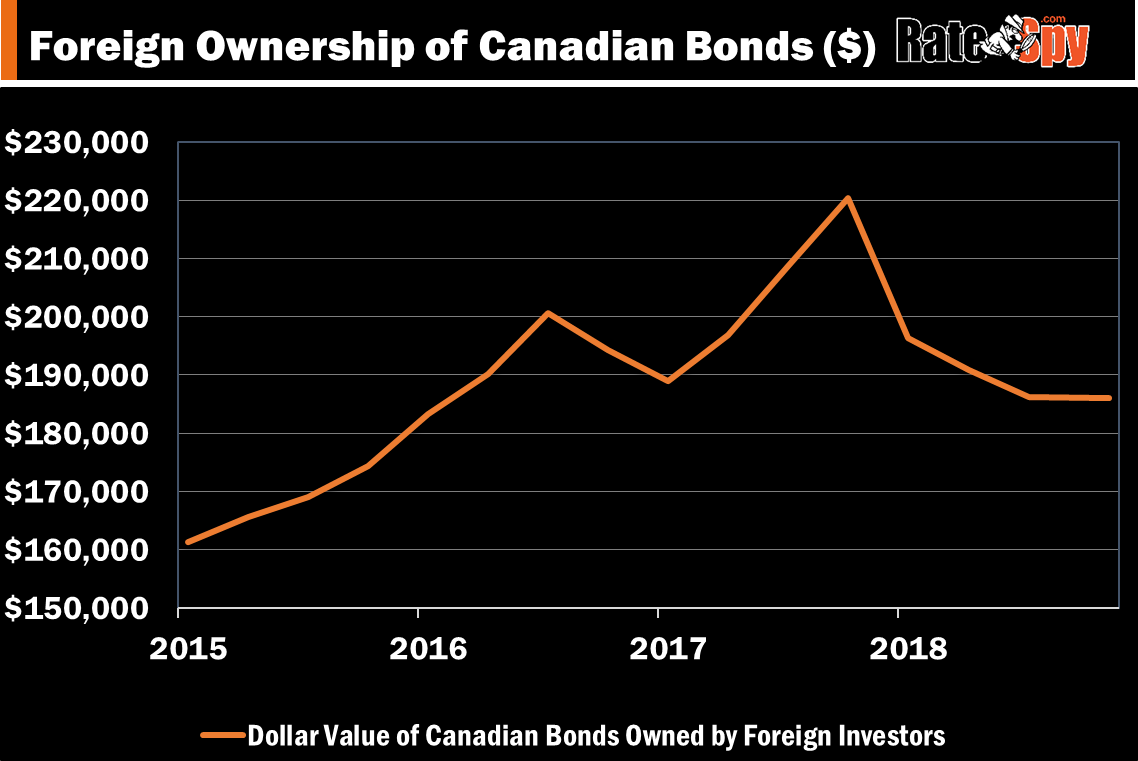

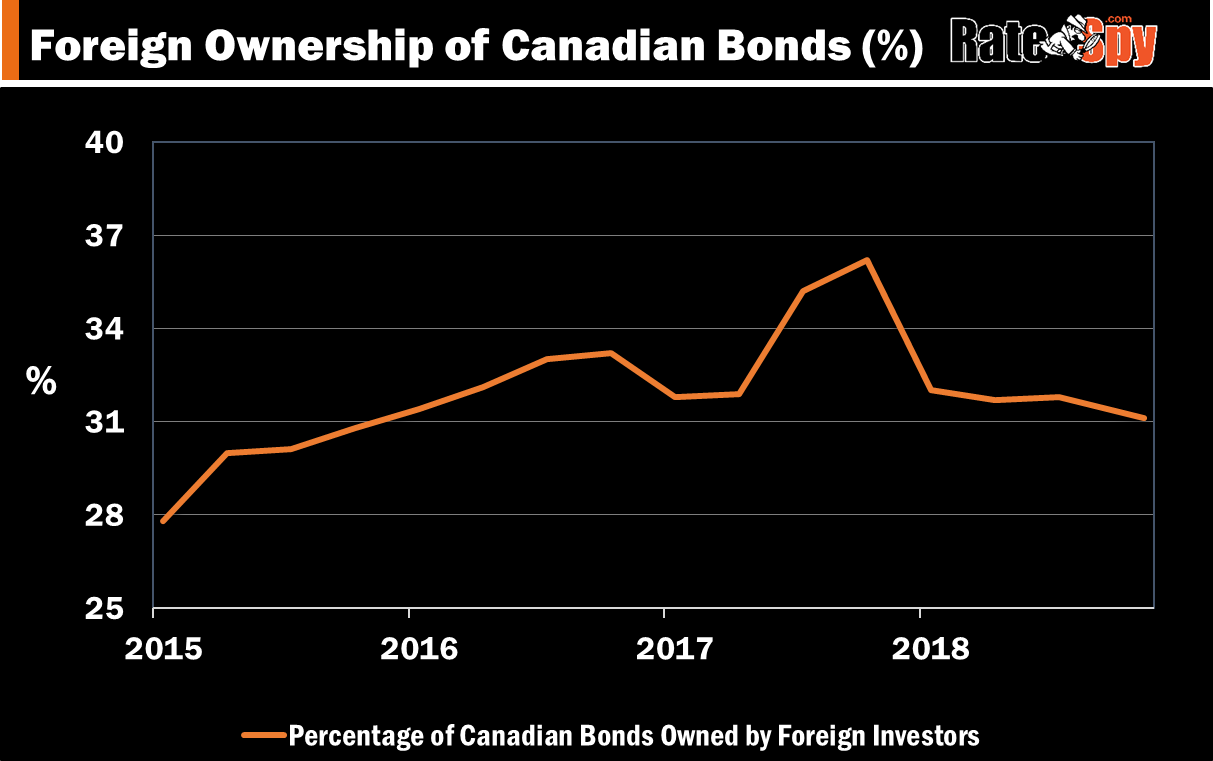

The latest data shows that foreigners, who own 30% of Canada’s bond market, have been shedding positions in the last year and a half. Here are the charts:

These are government bonds denominated in Canadian dollars. In millions. Source: StatsCan

These are government bonds denominated in Canadian dollars. Source: StatsCan

Overseas investors have been losing confidence in Canada’s economic position. They’ve also lost some confidence in the Canadian dollar. And that’s a problem — because the value of our loonie impacts their investment returns (since investors must buy Canadian dollars to buy Canadian denominated bonds).

What’s the Effect?

The news about Japan buying our bonds should be welcome for anyone rooting for rates to stay low. “We see these flows (from Japan) being an important dictator of near-term curve directionality,” CIBC wrote.

Without a doubt, overseas buying saves Canadians money. Between 2009 and 2012, for example, foreigners bought $150 billion of GoC bonds. That pushed down our 10-year yield by 100 basis points, estimates the Bank of Canada.

Without a doubt, overseas buying saves Canadians money. Between 2009 and 2012, for example, foreigners bought $150 billion of GoC bonds. That pushed down our 10-year yield by 100 basis points, estimates the Bank of Canada.

In practice, another country ramping up Canadian bond purchases by $10 billion today could easily move the mortgage market. The effect wouldn’t be massive—we’re probably talking 5 bps or less depending on how concentrated the buying is in 5-year maturities. But even a 3-4 bps move in rates translates into dollars and cents.

If, for example:

- new international demand pushed Canada’s benchmark 5-year yield down 4-bps

- and that transferred to a similar 4-bps drop in 5-year fixed funding costs

- and lenders passed it along to consumers…

…that would amount to potentially $500 in interest savings over five years on the average $265,923 mortgage.

For this and other reasons (like keeping the government’s borrowing costs lower and keeping inflation contained), mortgagors are well-served if our currency and bonds remain attractive abroad.

log in

log in

10 Comments

This is eye-opening although I wonder what Canada can do to attract more foreign investors. Our rates are so dependent on the US.

Are Canadian bonds issued in overseas markets included? When the banks are able to hedge the CAD/EUR, they can significantly increase their mortgage spreads given the extremely low rates in the Euro zone.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/record-start-to-covered-bonds-sales-leads-way-for-canadas-banks/article33565258/

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-04-02/beware-the-buyer-s-strike-in-european-corporate-bonds

This data from StatsCan is for CAD-denominated bonds only, the more direct influencers of domestic mortgage funding costs.

One thing politicians can do is stop giving our taxpayer money away to every social cause in the book. People slave 7 months a year to pay taxes in this country. It’s disgusting. All so government can piss away our money on wasteful social programs. How about using that money for good, like paying down the debt! Maybe fewer handouts would motivate people to work two jobs to provide for themselves instead of living off our backs. The know it alls in Ottawa always preach about how people shouldn’t take on so much debt. Meanwhile all they do is take on debt: https://tradingeconomics.com/canada/government-debt

They are nothing but hypocrites and the bond market is wising up to them.

“…given fixed mortgages are partially funded in the bond market.”

This is a common misconception. Banks literally create money out of thin air whenever they make “loans.”

Straight from the Bank of England (Money creation in the modern economy, 2014)

“The principal way in which [deposits] are created is through commercial banks making loans: whenever a bank makes a loan, it creates a deposit in the borrower’s bank account, thereby creating NEW MONEY. This description of how money is created differs from the story found in some economics textbooks.”

NOTE: banks don’t lend deposits, they don’t lend reserves (fractional reserve banking), and they don’t rely on the bond market. Banks literally create money out of nothing!

Pretty much everyone with any rudimentary knowledge of mortgage funding knows that banks use swaps, Canada Mortgage Bonds, banker’s acceptances, deposit notes and mortgage-backed securities to fund mortgages. These are all fixed income (bond market) instruments. How can you possibly call it a misconception to say mortgages are partially funded in the bond market?

Add covered bonds and ABCP to the list of bond market funding vehicles. Even things like brokered deposits are closely tied the bond market rates. This guy is completely out to lunch to suggest banks don’t rely on the bond market.

“Pretty much everyone with any rudimentary knowledge of mortgage funding knows that banks use swaps, Canada Mortgage Bonds, banker’s acceptances, deposit notes and mortgage-backed securities to fund mortgages.”

This is what I used to think, but the central banks seem to disagree. If you don’t believe the BANK OF ENGLAND, there is also the BUNDESBANK and the CENTRAL BANK OF NORWAY.

“…BANKS CAN CREATE BOOK MONEY JUST BY MAKING AND ACCOUNTING ENTRY: according to the Bundesbank’s economists, ‘this refutes a popular misconception that banks act simply as intermediaries at the time of lending – ie that banks can only grant credit using funds placed with them previously as deposits by other customers’. By the same token, excess central bank reserves are not a necessary precondition for a bank to grant credit (and thus create money).” (Bundesbank: How money is created, 2017-04-25]

“…BANKS CREATE MONEY OUT OF NOTHING and withdraw it when loans are repaid.”

(Central Bank of Norway, 2017)

JohnM

You are referring to leverage. Just because banks leverage their assets and capital to lend doesn’t mean lenders do not fund some mortgages in the bond market.

“You are referring to leverage. Just because banks leverage their assets and capital to lend doesn’t mean lenders do not fund some mortgages in the bond market.”

The capital ratios (or reserve requirements) are external constraints on banks imposed by government regulatory bodies. But these have nothings to do with the mechanism by which banks grant credit.

For a detailed explanation, see

How do banks create money, and why can other firms not do the same? An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking

Richard A. Werner (USouthampton, UK)

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2014.10.013

The short-hand version is that

1. banks “purchase” the loan agreement and record it as an ASSET on their balance sheet.

2. banks disburse the loan by reclassifying their obligation as a “Customer Deposit LIABILITY” on their balance sheet.

Thus, by the magic of double-entry bookkeeping banks create money out of nothing whenever they issue “loans”. This is how over 95% of our money supply is created.

In the banking industry, the terminology is “LOANS CREATE DEPOSITS”.

As an example, at the height of the 2008 financial crisis, Credit Suisse and Barclays were both insolvent (like all the other banks). But the brain trust at Credit Suisse and Barclays remembered that banks create money out of nothing. Despite being insolvent, Credit Suisse lent SFr 10 billion and Barclays lent USD $15 billion to the Emir of Qatar which were used to purchase shares in Credit Suisse and Barclays allowing both banks to recapitalize and avoid public bailouts.

Credit Suisse gave Qatar loan during crisis (Financial Times, 2013)

https://www.ft.com/content/e5b472f2-6c87-11e2-b73a-00144feab49a

Barclays and Former Executives Charged in Qatar Fund-Raising (NY Times, 2017)

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/20/business/dealbook/barclays-executives-charged-fraud-qatar.html