Remember the days of:

- VCRs

- Paper maps

- Beepers

- Being able to rely on banks lowering prime rate when the Bank of Canada cut its overnight rate?

Well, times change. And so has the pressure on banks to grow earnings each quarter.

Falling rates and a flattening yield curve have squeezed bank profitability, leading them to resort to unconventional earnings tactics. One of those tactics is a major annoyance to variable-rate fans everywhere: banks pocketing a portion of Bank of Canada rate cuts.

When it All Started

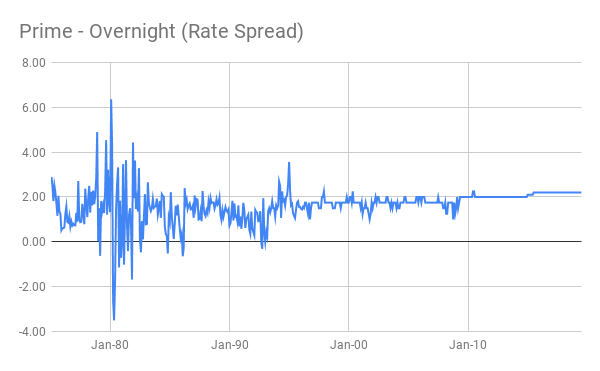

Way back when (in the 1990s and early 2000s) the spread between prime rate and the BoC’s overnight rate used to fluctuate around 1.75 percentage points. It did that for a decade and a half.

Then came the Financial Crisis, where things changed for the worse (for borrowers). Prime rate creeped up, rising to 2.00 percentage points above the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate.

Then, in 2015, it happened again. With the Bank of Canada cutting rates twice by 25 bps (50 bps total), banks dropped prime rate only 30 bps, keeping 20 for their troubles. As a result, the benchmark prime rate spread climbed to a two-decade high of 2.20 percentage points above the overnight rate. That’s where we stand today.

Will Banks Do It Again?

If our unscientific Twitter poll is right, they will.

Three out of four respondents have little faith that banks will convey the next BoC easing in full to consumers.

Opinion poll:

What is the probability that Canada’s big banks pass along the next Bank of Canada rate cut in full when lowering their prime rate?

— RateSpy.com ?? (@RateSpy) July 22, 2019

And, banks argue that we shouldn’t blame them.

They’re dealing with:

- lower loan growth

- heightened credit risk (since we’re nearer to the end of the business cycle)

- more competition for deposits (raising their funding costs)

- more competition from online mortgage competitors

- a flat yield curve (which makes it harder for banks to profitably borrow short to lend long), and

- falling rates (banks make more for a year or two after rates drop but net interest margins ultimately follow rates lower — largely because loans are paid off or renewed at lower interest rates).

Banks make money-making seem easy. But in fairness, it’s harder than ever. And trust us, we’re not playing violins or shedding tears on their behalf. It’s just a fact. And folks have to acknowledge that so they can strategize accordingly.

If we’re lucky, Canada’s Big 6 may lower prime rate in line with the BoC’s next cut. But for the reasons above, they may not.

One thing’s for certain, however. The more our central bank eases rates, the more likely big banks will “pilfer” some of the spread (i.e., not lower prime rate in parallel with the BoC).

Variable. Why Bother?

That question is increasingly on the minds of Canadian mortgage shoppers.

That question is increasingly on the minds of Canadian mortgage shoppers.

And it’s a hard one to answer. Informed borrowers understand the historical edge of variable mortgages, but the research that established that edge never contemplated:

- banks would not match BoC rate cuts

- there’d be a long-term downtrend in rates

- rates would approach zero

- central banks would be cutting rates in period of full employment (arguably creating tail risk of an inflation spike—and higher rates—in the future).

If Canada is indeed entering a new longer-term rate-cutting cycle—contrary to the Bank of Canada’s expectations—then giving up 10 bps here or there to banks isn’t a reason not to go variable. If the BoC cuts twice, for example, and banks keep 10 bps each time, you’re still ahead by choosing variable (assuming you’re a new borrower and get a deep discounted rate).

But given we can’t count on banks to lower prime in 25 bps increments with the BoC, if you can save 15-20+ bps with a fixed rate upfront, the odds of success are less slanted in variable’s favour.

Moreover, with psychology being what it is, most borrowers would rather avoid risk than take it. So it’s no wonder that variables have lost their lustre. Bank’s stinginess with prime rate is only making that worse.

The value for many is in shorter fixed terms. If you can find a rate that’s far below a 5-year fixed (like the 1.99% DUCA 2-year fixed rate for high-ratio mortgages), that shifts the odds well back in your favour. So keep rooting for short-term fixed rates to drop. And if they do, consider them a good alternative to variables and sidestep this prime rate debate altogether.

Sidebar: In a few notable cases, lenders have taken it upon themselves to increase prime rate independent of Bank of Canada rate moves. The most notorious case was TD Canada Trust a few years back. In 2016, TD unilaterally hiked its prime rate 15 bps, arbitrarily raising borrowing costs for all of its existing variable-rate mortgage customers.

log in

log in

2 Comments

Even though 5yr fixed rates are lower than variable, I still think variable rates are worth serious consideration. As long as it is a variable rate that you can lock in at the lender’s discretionary fixed rate, you get to hedge your bets.

I think rates will continue to move lower over the next year. If your lender doesn’t pass on the full reduction in prime, you can switch to a fixed.

Last month BMO quoted 2.94% for a 5yr fixed switch from 5yr variable on a rental property with a 30-year amortization. That’s the same as the best rate they were offering on a new rental purchase.

No doubt, variables are still worth considering for the right type of well-qualified risk-tolerant borrower.

Regarding the conversion “option,” keep one thing in mind. Locking in a variable at most lenders gets you a subpar fixed rate—well above the industry’s best rates for that given term. Most lenders do not offer their best discretionary rates on conversions. Not to mention, most borrowers miss-time rate locks (are late at locking in).