It’s no secret. Many homebuyers that had no trouble qualifying for a mortgage in 2017 are finding big challenges in 2019. As we wrote yesterday, the government’s harsher mortgage “stress test” is a key reason why.

It’s no secret. Many homebuyers that had no trouble qualifying for a mortgage in 2017 are finding big challenges in 2019. As we wrote yesterday, the government’s harsher mortgage “stress test” is a key reason why.

The problem is exacerbated by the banks’ refusal to lower their posted 5-year fixed rates, despite a 55-basis-point drop in the 5-year bond yield since the stress test rate last changed.

But more and more homebuyers are finding workarounds, and they’re finding them at credit unions and non-bank lenders.

While banks make you prove you can afford a rate that’s up to 200+ basis points higher (5.34% or more), some credit unions are now qualifying borrowers in the mid-3% range.

On a $100,000 family income, choosing a credit union can get you approved for up to $118,000 more house. In some cities, that additional buying power could save you 10-20 minutes of commuting time, get you an extra bedroom, a bigger lot, or more.

We’re not going to name these credit unions and draw more attention to them, but experienced mortgage brokers know who they are if you’re curious. To take advantage of their offers, be willing to pay an interest rate that’s 25 to 50+ bps higher than the best big bank rates. That’s partly why only a small slice of buyers (our guess is less than 2-3% by volume) are resorting to such products.

CMHC’s Top Dog Doesn’t Like It

The CEO of Canada’s housing agency, Evan Siddall, is not excited about provincially regulated credit unions not having to use the federal banking regulator’s uninsured mortgage stress test.

Last April he said:

“This is why we are asking credit unions – along with all other participants in our securitization programs – to provide information on their entire mortgage portfolio – not just the portion insured by CMHC. As a systemically important financial institution, we need to understand the full extent of the risks we are exposed to through our securitization guarantees. The data we have requested will allow us to better understand developments and risks in the uninsured space, including trends and the migration of risks between program participants.“

Last year CMHC told institutions participating in its mortgage-backed securities program that they had to provide data on their uninsured mortgage businesses. The housing agency’s stated reason: “To aid in mitigating exposures to participants in the NHA MBS program, and more generally to support CMHC’s legislative mandate of contributing to the stability of the mortgage market.”

Critics from small and medium-sized lenders cried foul, saying the feds are trying to root out which non-federally regulated lenders let borrowers qualify without the federal stress test. With that information, industry sources speculate that CMHC could restrict access to its MBS program if a lender doesn’t stress test all mortgages using bank rules (even though such lenders aren’t directly bound by OSFI’s stress test).

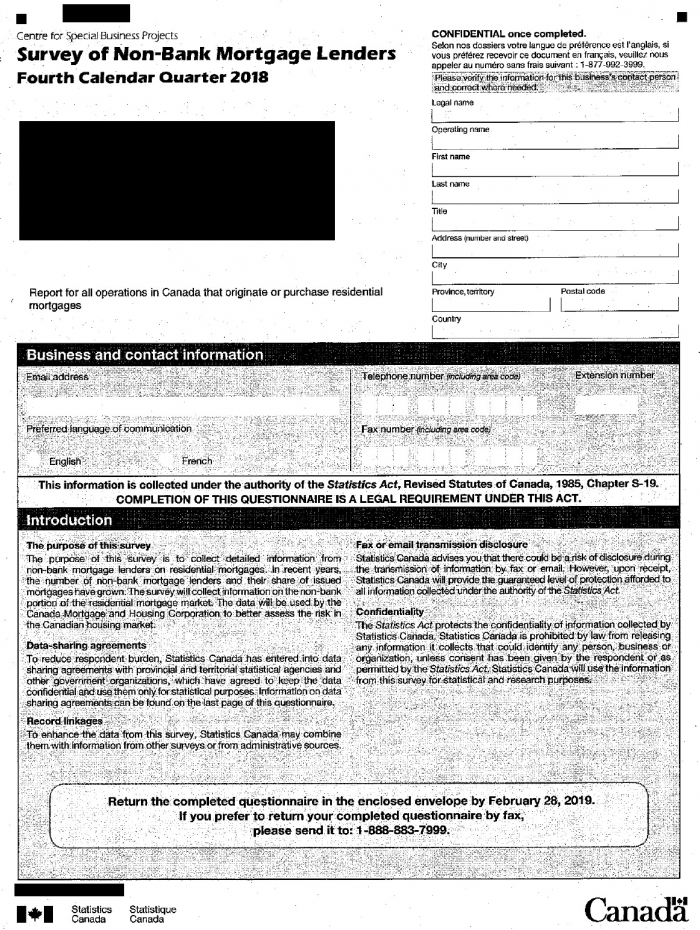

CMHC also engaged Statistics Canada to conduct a separate survey of all non-bank institutions that provide mortgage lending in Canada, including insured loans. The information is being collected under the Statistics Act with the survey stating that: “The data will be used by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation to better assess the risk in the Canadian housing market.”

It’s Not the Data. It’s What They Do With It

The Department of Finance and CMHC want centralized stats on the entire Canadian mortgage market, and that’s fantastic. Finally, we’ll have an up-to-date view of just how high- or low-risk the mortgage market really is. Much of the data will be made publicly available later this year.

The question is, will the federal housing agency use this data as leverage to force provincially regulated credit unions (and mortgage finance companies) to impose the federal stress test on all borrowers? In such a scenario, an approved issuer that didn’t comply could theoretically lose securitization privileges.

If this happened, it would undoubtedly:

If this happened, it would undoubtedly:

A) Hurt lenders’ ability to fund themselves (raising costs on consumers and potentially making those lenders noncompetitive in the prime lending market), and

B) Prevent lenders from offering higher-risk lending products (limiting consumers, who run into hard times, from refinancing themselves out of debt holes—ultimately leading to more defaults, insolvencies and panic home sales).

Supporters say that by Ottawa compelling all lenders into stress testing all their borrowers at 200+ basis point higher rates, it makes for a more stable housing market.

Critics would call it government over-reach. In such a case, access to competitive borrowing costs could plummet for borrowers who were good credit risks but merely had higher debt ratios (higher based on the new bar, that is, which CIBC and others argue is too high).

The one thing you can say for sure is that everyone should want a safe housing market and no one should want economically damaging regulatory overkill. To that, we’d add: “especially if it means low-default-risk consumers lose even more refinancing options.”

log in

log in

The CEO of Canada’s housing agency, Evan Siddall, is not excited about provincially regulated credit unions not having to use the federal banking regulator’s

The CEO of Canada’s housing agency, Evan Siddall, is not excited about provincially regulated credit unions not having to use the federal banking regulator’s

3 Comments

Canada was once a true free enterprise democracy. Now, every year that goes by financial regulators flout freedom, enterprise and democracy a little more. Henry Paulson predicted the future in one sentence when he said, “There is a very real danger that financial regulation will become a wolf in sheep’s clothing.”

so this is what doesn’t add up, not even remotely add up: if only a “small slice” of borrowers who fail a bank B20 test are willing to pay 25 to 50bps to get a larger non stress tested loan from a credit union, then why on gods green earth would a larger group of borrower be willing to pay 400 to 700bps more to go to a MIC, which is what everyone, including Ben Tal seems to be suggesting is happening. Can you reconcile these somewhat contradicting points? I sure can’t.

Hi David,

CIBC says MICs and privates grew two percentage points (by volume) in the last couple years. It’s material but still not a giant number on an absolute basis.

MICs are getting more business from a variety of customer types and for a variety of reasons (OSFI-regulated non-prime lenders imposing the stress test and tougher doc standards, general interest rate increases, etc.)

Separately, for many borrowers, the spread between MIC rates and prime rates is often lower than 400-700 bps. Part of it is because MIC borrowers generally get shorter mortgages (e.g., a 1-year term) than prime borrowers (most of which get 5-year terms).