A quick briefing on recent mortgage rate developments:

- Higher Rates on the Radar: The market has now fully priced in a rate hike this year, based on the yields of interest rate derivatives. “Clearly this is no longer an economy that requires emergency-level interest rates,” says TD. Both it and CIBC predict the first 25 bps rate bump in October. But some analysts think it could happen as soon as the July 12 or September 6 meetings, given the BoC’s sudden urgency.

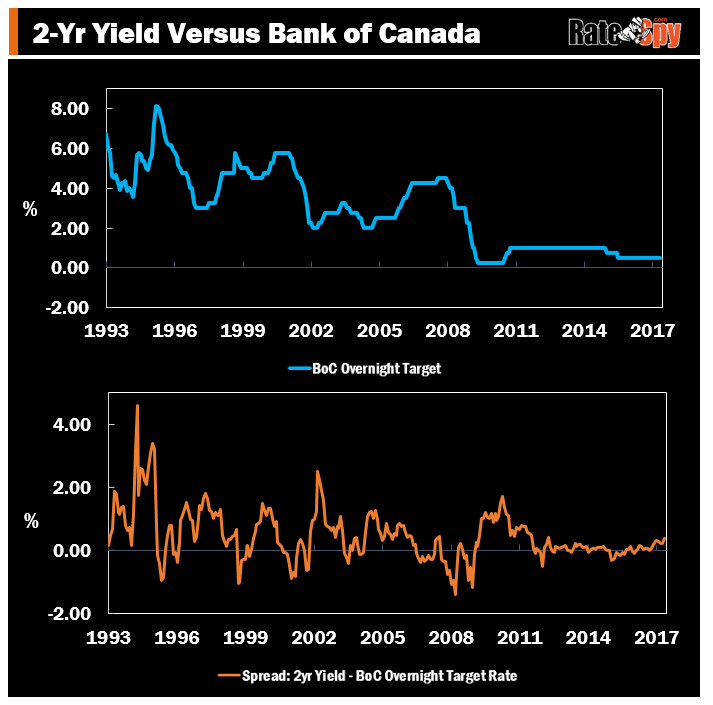

- What the Market Says: Two-year government bond yields typically lead Bank of Canada rate changes. That’s why the 2-year yield shot up following the BoC’s hawkish comments last week. The last time it was this high, the Bank of Canada’s key rate was 50 bps above today’s level.

- The Ceiling on Rates: The BoC’s previous rate hike cycle lasted just 75 bps before rates U-turned lower. Given Canada’s tipsy housing market, consumer debt burden, feeble wage growth, risk of an oil selloff, U.S. trade uncertainty and lacklustre exports, the BoC may choose to limit its increase(s) to 50-100 bps, then pause for a year or more to see the effects.

It Could Soon be Prime Time: When the BoC does tighten, variable-rate mortgagors will be watching to see if the Big 6 banks:

It Could Soon be Prime Time: When the BoC does tighten, variable-rate mortgagors will be watching to see if the Big 6 banks:

- lift their prime rate only 15 bps — to match their last two prime rate cuts, or

- stick it to borrowers with a full 25 bps hike (to match the BoC).

.

Most industry watchers we’ve chatted with expect the latter.

Rule Change Alert: OSFI is considering tweaks to the underwriting bible for Canadian banks (a.k.a., “Guideline B-20”). Proposed changes to B-20 will be published for public consultation in the coming weeks, writes the Bank of Canada. The biggest mortgage question of the year will then become: Will OSFI require banks to make all prime borrowers, even those with 20%+ equity, prove they can afford a payment at the posted 5-year fixed rate? The government already mandates this “stress test” for all insured borrowers. Bank competitors charge that OSFI would be creating a double standard and showing favouritism if it didn’t impose the same requirement on banks.

Rule Change Alert: OSFI is considering tweaks to the underwriting bible for Canadian banks (a.k.a., “Guideline B-20”). Proposed changes to B-20 will be published for public consultation in the coming weeks, writes the Bank of Canada. The biggest mortgage question of the year will then become: Will OSFI require banks to make all prime borrowers, even those with 20%+ equity, prove they can afford a payment at the posted 5-year fixed rate? The government already mandates this “stress test” for all insured borrowers. Bank competitors charge that OSFI would be creating a double standard and showing favouritism if it didn’t impose the same requirement on banks.- Regulatory Pain: The Bank of Canada is acknowledging the cost that the Department of Finance’s recent insurance and capital rules are having on the mortgage market. In its recently released Financial System Review (FSR), the bank says: “Lenders are charging a…premium of around 10-20 basis points (bps) on some mortgages that are no longer eligible for mortgage [default] insurance.” If we assume the mean (15 bps), that’s boosted the cost of many uninsurable mortgages by at least $1,400, every five years. The average mortgage balance in Canada is $201,000, says Manulife Bank.

- Quote of the week: The vast majority of variable-rate mortgagors can handle rate hikes in stride, says mortgage DLC broker Dustan Woodhouse, who notes: “…In light of the federal government’s implementation of the 4.64% qualifying stress test…there is effectively a 2.50%-point buffer between [variable mortgage rates] and the qualifying rate…the equivalent of approximately 10 Bank of Canada rate hikes.“

log in

log in

Quote of the week: The vast majority of variable-rate mortgagors can handle rate hikes in stride, says mortgage DLC broker Dustan Woodhouse, who notes: “

Quote of the week: The vast majority of variable-rate mortgagors can handle rate hikes in stride, says mortgage DLC broker Dustan Woodhouse, who notes: “

6 Comments

I think we’re long overdue for at least one bump up in rates. It just seems every time we near that point some new data comes out to stoke fears about the economy all over again.

What would you say are the odds of a 50 bps hike by the end of the year?

Very true Tony.

Regarding two hikes this year, if the BoC raises in one of the next two meetings, the odds are probably greater than 50% they’d hike in one of the final two meetings.

The market is pricing in a 100% probability of at least one hike this year. But if oil dives below $40, that probability could easily fall.

I’m confused, I’ve been watching rates for a little while now and I’ve seen some shorter terms going up while rates for some of the longer terms (7 and 10 year) are falling. Is this normal?

Hi Hopeful, Part of the reason is that the yield curve is flattening. It’s not typical, but it happens when investors lose some confidence in the economy.

.

Hi Spy,

In this environment is the 2-year-fixed more desirable than the 5-year-variable if rates are the same and all else is equal?

Great question Max.

The pros of a 2-year are:

* Your rate is locked in for longer — which is beneficial if rates are rising

* It lets you renegotiate sooner — which is helpful if you expect to add more money to your mortgage in a few years

* It lowers the odds you’ll have to break your mortgage early and pay a penalty

The cons of a 2-year are:

* Many lenders don’t let you switch into a 2-year without legal fees — whereas a 3-year term or longer usually permits “free switches”, albeit you always pay the prior lender’s discharge fee

* You have to go through the renewal process again in 2-years — this is mostly an inconvenience unless you can’t qualify for some reason

* Your rate is locked in — which costs you money if rates are falling

* Unlike a variable, you generally cannot lock a 2-year term into a longer fixed rate before maturity — which is usually a bad idea anyway

* The penalty can sometimes be higher than a variable rate (i.e., you’re potentially looking at an IRD penalty instead of a 3-month interest penalty, but the short term mitigates this risk somewhat)

All this said, with everything else equal and given the stable to (arguably) rising rate outlook, most well qualified borrowers would do well to consider a 2-year fixed over a variable.