It’s remarkable how much people focus on the Bank of Canada’s “neutral rate” nowadays.

It’s remarkable how much people focus on the Bank of Canada’s “neutral rate” nowadays.

It has become a lighthouse in the rate fog. People rely on it to gauge how far we are from “normal” interest rates.

If you’re not familiar with the “neutral rate,” it’s basically the theoretical overnight rate that neither accelerates nor slows the economy and inflation. Last week, the BoC chopped its estimate of neutral by one-quarter point. Such adjustments happen only once a year, so it was a big deal.

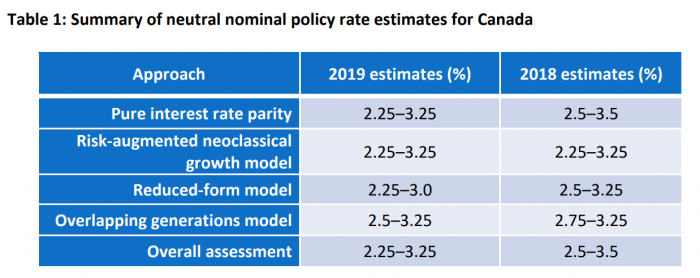

The bank now says, “the Canadian neutral rate likely lies in a range of 2.25 to 3.25 per cent…”

That range is a measly one-half point above where Canada’s 1.75% policy rate now stands. In other words, “normal” rates are arguably not that far away.

The bank attributed the drop in its long-run benchmark rate to “a lower assessed global neutral rate” and “improved modelling techniques.” Essentially the economy’s cruising speed is less than previously expected.

You Can’t Pin Down Normal

On Tuesday, BoC Governor Stephen Poloz reminded everyone that “normal” (i.e., neutral) rates are a moving target. He said the bank’s neutral estimate could increase again “one day.” And no doubt it will, even if it has to drop first before rising.

Such fluctuations don’t seem to dissuade people from using the BoC’s neutral estimate as a guidepost for how high rates should go.

And all of this is of particular interest to those considering variable mortgage rates. Their fixed vs. variable decisions largely boil down to comparing the risk of floating rates to their historical outperformance.

Such borrowers will now find incrementally more comfort in the bank’s rate projections. BoC models now imply that it’s highly unlikely rates will exceed 3.25% in this rate cycle, at least not for any significant amount of time.

Source: Bank of Canada

Trust the Models, to an Extent

You’ll want to take these estimates with a pound of salt. The BoC has virtually unlimited analytical resources, but still its models on inflation, GDP and rates are about as accurate as hurricane predictions (which, interestingly enough, are off by 100 miles on average).

In fact, “The BoC’s inflation projections since 2010 have shed virtually no light on where inflation was heading,” wrote economist Ted Carmichael. His research suggests the BoC has an inflation “projection error equal to 90-100% of the standard deviation,” which makes its projections “not of much value.”

But, as imprecise as the bank’s models may be, they are not so drastically inaccurate as to call into question the 3.25% upper bound of its neutral rate estimate. The BoC sets the extremities of its rate projections with great care, so as to encapsulate unexpected events. Hence, one might consider this 3.25% a likely worst case for where the overnight rate levels out in the current business cycle. That should be at least somewhat comforting to mortgage shoppers, many of whom avoid floating rates for fear of runaway inflation and 1981-style rate hikes.

Assuming even one of the BoC’s four rate models is in the ballpark, it’s a way for borrowers to reasonably quantify their interest cost risk. For mortgagors taking a floating rate today, the country’s most respected economic source is implying little more than 150 basis points of rate-hike risk.

That kind of move would lift your payment about $241 a month on a standard $300,000 adjustable-rate mortgage at 2.99%. It would be painful, but not debilitating for most—given virtually all floating-rate applicants are now stress tested at 200-basis-points higher rates.

Mind you, seeing anywhere near that 150 bps of rate tightening would likely require sustained growth over 3.5% to 4.0% (a tall order for this economy) and/or an unforeseen inflationary shock (e.g., $125+/barrel oil). And, for what it’s worth, bond traders are betting there’s a far greater likelihood that the BoC’s 3.25% neutral rate ceiling is higher than where rates will peak this cycle.

log in

log in

4 Comments

My infallible expert opinion is that economists on government salaries have no clue how much rate increases are killing debt bloated homeowners. If this teetering economy survived another 1/2% of hikes I’d be surprised.

I found the bank’s previous neutral range to be a little high. Fundamentals didn’t seem to support it. At least they’ve brought it a little more in line with what (from this layman’s perspective) seems more realistic.

Any thoughts on whether we would be likely to see this range fall further, with the lower end hitting 2%?

Hey Alex,

The BoC trimming its lower estimate for neutral to 2% next April is unquestionably a possibility.

Our economy is in a long-term rut, seemingly anchored to 2%-ish growth (https://tradingeconomics.com/canada/gdp-growth-annual) and 2% inflation. Almost every reputable long-term forecast supports that expectation. And if that’s the world we live in, such numbers may not justify even a 50 bps real overnight rate (2.50% nominal rate).

One has to ask, what aspect(s) of Canada’s economy could push growth from the pathetic 1.2% the BoC projects this year to a sustainable 3%+?

Can we rely on:

> Oil? (only if we get pipelines built, and then only for the next 10-15 years — before consumption falls)

> Housing (maybe for a short sprint while supply catches up, but pricey housing is hurting non-housing consumption)

> Manufacturing (lol)

> Metals (no)

> Other exports (Poloz would like to think so but our balance of trade remains….sad)

So what does that leave? Commercial services, consumer goods, agricultural, forestry? They’d make too small of a net GDP contribution to matter in the next business cycle.

And then there’s the soul sucking reality of onerous taxes, the high cost of living in big cities and wage stagnation. Not enough people can get ahead. It’s that simple. And this has serious implications long-term for consumption and investment.

Which brings us back to the neutral rate…

Short of wild deficit spending, many analysts don’t believe the overnight target will ever touch “neutral” in this rate cycle. And it’s easy to see why.

Normally I’d take a variable because the Bank of Canada has proven it can keep inflation low. But fixed and variable rates are so close that its hard to justify gambling on prime rate. What to do?